Britain gave President Donald Trump a welcome fit for the king he often pretends to be.

It was a day draped in more golden gilt — on Queen Victoria’s state coach, which bore the president to Windsor Castle; on the tunics of mounted soldiers; and on a state banquet table — than Trump has plastered over Mar-a-Lago and the Oval Office.

The reality star president adores pageantry and being at the center of it. And the royals rolled out perhaps more pomp than he’s ever seen. Bagpipers and guards in bearskins marched in his honor, and at a white-tie feast, he dined between a king (Charles III) and a future queen (Catherine, Princess of Wales) inside the grandest property in the regal real estate portfolio.

“This is truly one of the highest honors of my life,” Trump said, responding to the king’s toast.

Of all the flattery foreign nations have showered on Trump, this might be the finest.

The British monarchy has practiced the art of the deal since long before Trump was born. His Majesty’s government wants shielding from Trump’s most mercurial instincts, a better tariff rate, investment for its slow-growth economy and cash to build a new artificial intelligence powerhouse. And it hopes to persuade Trump not to abandon Ukraine to his friend Vladimir Putin.

Yet Trump’s royal welcome was also a jarring fairytale. The way nations present themselves on such occasions can present an unflattering state of their health.

The rituals honoring Trump were those of a vanished empire. He wants to make America great again. Britain once was great, but now is deeply reliant on the United States for its defense and its economic well-being. It can lay on military pageantry on the lawns of Windsor but would struggle to deploy a viable force to Europe if Russia were to invade. In the 21st century, it’s selling 19th-century glories.

But there’s never been a US president so susceptible to royal buttering up.

With a twinkle in his eye, Charles recalled George Washington’s vow never to set foot in Britain. And more than two centuries ago, John Adams, the Founding Father and future president, wrote home about his distaste for bowing — as his nation’s first ambassador to Britain — before the king he’d helped lead a revolt against.

Trump wouldn’t recognize such reticence and self-awareness. Even so, the current sovereign didn’t seem to be aiming for irony when he said, “I cannot help but wonder what our forebears of 1776 would make of this friendship today.”

Trump’s comfort in the royal court was a commentary on an American head of state who seems more a throwback to indifferent all-powerful monarchs than to George Washington’s understanding that the greatest responsibility of power is knowing when to cede it.

Diplomacy is often distasteful. But Trump’s second state visit to Britain was the latest reminder that much of the world has decided that the only way to tame his bullying ways is to appeal to his vanity.

Optics aside, Trump’s visit to the UK represented a severe challenge for the government of British Prime Minister Keir Starmer, who won a huge landslide election victory last year — but has slumped into a deep political crisis.

Starmer has won plaudits for his handling of Trump. Britain escaped with a 10% tariff on its exports to the US — lower than the rate for the European Union, which Trump hates. And Starmer is a leading player in the “coalition of the willing” that hopes to offer post-war security guarantees to Ukraine after a peace deal, but that needs Trump’s support. He’s also agreed to boost defense spending to meet US demands, even if no one has a clue how he’ll pay for it.

But the unpopular Starmer is playing a dangerous game. Many Britons view Trump as a corrupt thug and believe his values are antithetical to those of the West.

Still, while he might be reviled, his populist politics are tightening their grip on the UK. The anti-immigrant Reform Party led by his friend Nigel Farage is leading the polls and could shatter generations of Labour-Conservative dominance at the next election.

Trump’s administration often seems to be interfering in UK politics. Vice President JD Vance enjoyed vacationing in the picture-postcard Cotswolds, but lambasts Britain over freedom of speech. Trump’s team is trying to force Britain to amend restrictions on racist or extremist online material to please US tech firms. At the weekend, erstwhile Trump ally Elon Musk called into a far-right rally in London and demanded a revolution.

Starmer’s balancing act became harder when he was forced to fire the UK ambassador to Washington Peter Mandelson, who helped plan the state visit, over his past friendship with Jeffrey Epstein. The debacle only focused more attention on the US president’s failure to shake off his own past friendship with Epstein. And the royals aren’t immune either. Prince Andrew, the second son of Queen Elizabeth II, was forced out of official duties because of his own links to the convicted child sex offender.

When protesters beamed images of Trump and Epstein onto the battlements of Windsor Castle Tuesday night, they were speaking for many Britons who don’t think Trump should have been invited at all. Their antipathy helps explain why Windsor — originally built as a fort — was a good place for the president to sleep.

London Mayor Sadiq Khan, a longtime Trump antagonist, wrote Tuesday in the Guardian that far from flattering the president, the UK should speak truth to power. “President Donald Trump and his coterie have perhaps done the most to fan the flames of divisive, far-right politics around the world in recent years,” wrote Khan, a member of the governing Labour Party.

Public distaste for Trump contrasts with the reception offered to his nemesis, President Barack Obama, during his state visit with Queen Elizabeth in 2011. But Trump is not the first commander in chief to be greeted with protests. President Ronald Reagan arrived in Britain in 1982 for a state visit and talks with Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher amid concern that his hawkish rhetoric would spark a war with the Soviet Union. Reagan was the first president to sleep at Windsor Castle, and the queen smoothed over the sensitivities of the visit by joining him in a horseback ride on the castle grounds that is now the enduring image of Reagan’s stay.

At the time, left-wing Labour Party MP Tony Benn recorded in his diary impressions that would be familiar to Trump skeptics 43 years later. “Reagan is just a movie star acting the part of a king, and the Queen is like a movie star in a film about Britain. Mrs Thatcher is an absolutely Victorian jingoist. I find it embarrassing to live in Britain at the moment.”

The sensitivities of Trump’s visit called for a careful pair of diplomatic hands. King Charles was for much of his life a figure of pity and fun in the UK, as he waited to get the top job as a 70-something. Many of his private views, like the need to fight climate change, clash with those of his guest. But the British monarchy is bound to official impartiality by constitutional convention.

And, since ascending the throne, Charles has shown deft political skills that go beyond those of his publicly apolitical mother. Mending post-Brexit angst, he spoke fluent German in Berlin and French in Paris. And as the king of England stood alongside Trump on the viewing stand at Windsor it was hard not to recall that, as the king of Canada, he visited Ottawa in May to affirm the country’s sovereignty following repeated demands by the US president that it become the 51st state.

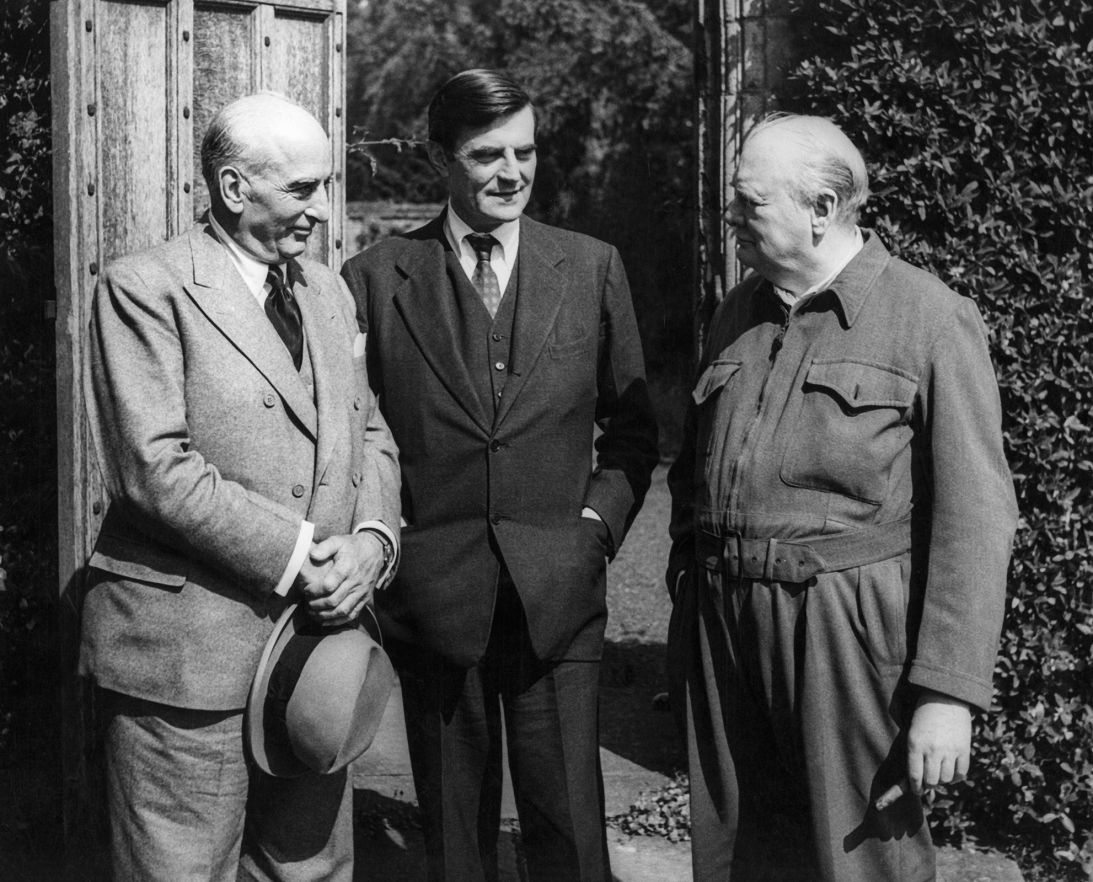

Charles’ political dexterity has been decades in the making. An early exposure to US presidents came when he helped his mother, Queen Elizabeth II, greet President Dwight Eisenhower at Balmoral Castle in Scotland in 1959. For an institution as image-conscious as the House of Windsor, it’s almost certain that the photo of the young heir in a kilt was included to send a sign of future continuity with the US and statecraft on which he drew Wednesday.

Trump will swap the grandeur of Windsor Castle for austere power politics on Thursday when he heads to Chequers, the official country house of British prime ministers, in Buckinghamshire, northwest of London. The relentless historical propaganda machine of the British state will have one last chance to shine.

Trump is expected to be shown archives related to Prime Minister Winston Churchill, a historical figure whom he reveres. The president made sure to mention in his state banquet toast that the bust of the great World War II leader — which the needy British press regards as a barometer of the “special relationship” through different presidencies — was restored to the Oval Office.

The focus on Churchill — whose legend has become a bullish avatar for British identity and a lament for lost power — is significant. The then-prime minister, discouraged by military defeats early in World War II, dined with the US ambassador to the UK, John Gilbert Winant, and President Franklin Roosevelt’s special envoy, Averell Harriman, one cold evening at Chequers in December 1941. After clocks struck 9:00 p.m., he reached for the radio to listen to the news on the BBC and caught the tail end of an item saying that Japan had bombed US navy ships in Hawaii. Moments later, a butler rushed into confirm the news of Pearl Harbor, the attack that drew the United States into World War II.

Churchill, who knew only US involvement could defeat the Nazis and imperial Japan, wrote in his post-war memoirs that he “slept the sleep of the saved and thankful” that night. He recounted that he’d never believed naysayers who predicted that political disunity, recurrent elections, a wariness of foreign wars and a tendency to be a “vague blur on the horizon to friend or foe” would mean that Americans — “a remote, wealthy, and talkative people” — would never come to the rescue of the old world. His description of US pre-war isolationism now reads like a striking summation of Trump’s “America First” policies.

The “special relationship” has often been taken more seriously in London than Washington. But after King Charles on Wednesday noted that “tyranny once again threatens Europe,” Trump is being watched for signs that he really means his claim that “special” doesn’t do the relationship justice.

Britain hopes he goes home sharing sentiments that FDR expressed to Churchill over a crackly phone line on the night of Pearl Harbor.

“We are all in the same boat now.”